https://theconversation.com/the-biological-reason-why-its-so-hard-for-teenagers-to-wake-up-early-for-school-88802

The biological reason why it’s so hard for teenagers to wake up early for school

In societies the world over, teenagers are blamed for staying up late, then struggling to wake up in the morning. While it’s true that plenty of teenagers (like many adults) do have bad bedtime habits, researchers have long since proven that this global problem has a biological cause.

In 2004, researchers at the University of Munich proved that teenagers actually have a different sense of time. Their study showed that the 24-hour cycle which determines when you wake and sleep gets later during your teens, reaching its latest point by the age of 20.

After 20, the body’s waking and sleeping times gradually get earlier again, until at 55 you naturally wake about the same time as you did when you were 10. The link between the movements of this biological clock and the process of puberty was so strong that the researchers suggested this “peak lateness” at the end of the teenage years could be the biological marker for the end of puberty.

Sleep deprived

At about the same time the Munich study came out, Russell Foster at the University of Oxford made a key breakthrough in the neuroscience of time. By raising blind mice, Foster was able to show that all mammals’ sleep times depended on sunlight only. This means that biological time – which determines when you feel sleepy – is different from social time, which is set by clocks and customs about when things should be done.

When biological time and social time clash, it can lead to sleep deprivation. The social starting times for school and university – typically between 7.30am and 8.30am – are too early for teenagers the world over. The biological changes that teenagers go through mean they need to go to bed later, wake up later and get up to eight or nine hours of sleep.

As it stands, many teenagers are losing two to three hours of sleep every school night. As Steven Lockley at the University of Harvard concluded, this is systematic, unrecoverable sleep loss – and a danger to teenagers’ health.

An easy fix?

The solution is simple in theory: starting times should be adjusted to reflect the fact that teenagers need later starts as they get older. But in practice, there are three major challenges: proving that early starts directly damage teenagers’ health, identifying the best starting time, and overcoming education officials’ reluctance to change traditional early starts.

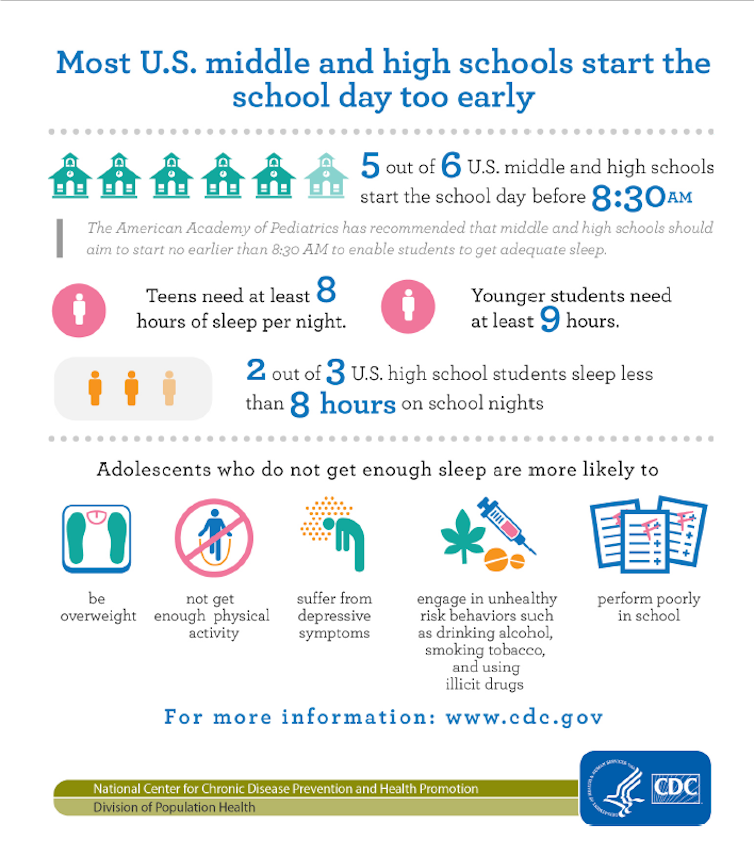

The US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention has drawn together many scientific studies to demonstrate that US schools should set later starting times. There is extensive medical evidence about the harms of starting school or university too early: doing so places teenage students at greater risk of obesity, depression, drug use and bad grades.

The American Medical Association now recommends that no classes for teenagers should begin before 8.30am. Yet early starts are still common in many countries around the world, among them Australia, UK, France and Sweden. There is further evidence that later starts are even better: studies show there are clear health benefits for 13 to 16-year-olds who start school at 10am.

Mariah Evans at the University of Nevada, Reno used new methods to identify the best times for teenagers aged 18 to 19. Her conclusion was dramatic: much later starting times of 11am or even 12pm are best for cognition.

Schools and parents all over the world need to change how they treat teenagers: rather than blaming them for being sleepy in the mornings, let them wake and sleep later to match their biological time. By starting schools and universities later we’ll raise safer, healthier and smarter teens at no real cost. It’s only a matter of time.